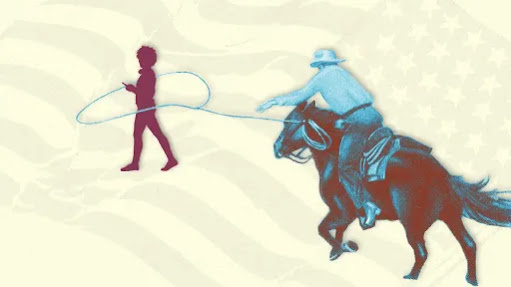

Institutional Racism: What It Is, Why It Persists, and What You Can Do About It

From health care to housing to education to employment, institutional racism is everywhere. The impact of institutional racism is far-reaching; it is a vicious cycle that takes a toll on individuals and society. Here's an overview of this historic and still prevalent form of discrimination that disproportionately affects the Black community.

What is institutional racism?

Institutional racism, also known as systemic racism, is maintained by the policies and power structures that have their roots in white privilege. While interpersonal racism shows up in the individual biases we hold for and against others based on race, institutional racism is embedded into the structures of our society—leading people of different races to have different outcomes when it comes to housing, employment, health, finance, and education.

Here's an example: If a white hiring manager decides not to hire a Black job applicant because he doesn't think that Black people work as hard as people from other backgrounds, that would be an example of interpersonal racism. However, if a company's practice is to not consider applicants from a specific neighborhood school (e.g. predominantly Black public schools in impoverished areas that have long been inadequately funded), that would be an example of institutional racism.

"Institutional racism is different and more implicit than interpersonal racism. It's come to the forefront of the national conversation after the murder of George Floyd and the protests for racial equity across the country last year," Beth Beatriz, PhD, a specialist in health equity research and an advisor at ParentingPod.com who lives in Boston, tells Health.

Nance L. Schick, a New York-based employment attorney and compliance and diversity training specialist tells Health that institutional racism has presented itself more subtly in recent years than in America's past. "What was once overt discrimination is now more covert and often hidden until someone speaks up," says Schick.

Institutional racism used to be publicly encoded into legislation across the country, thanks to legal segregation and Jim Crow laws. Today, institutional racism is not as frequently identified by clear policies and signage. However, biases in favor of white people still exist in more coded forms, says Schick. "Declaring certain hairstyles 'unprofessional' historically restricted qualified Black candidates from gainful employment," she says. "Despite the CROWN Act of 2020 (which prohibits discrimination based on hair texture or style), there are still employers who have restrictions on hair, in particular dreadlocks and natural African-American hair." None of these are inherently racist, but they can have an unfair outcome in Black communities, she adds.

How does institutional racism affect the US?

Nora V. Demleitner, a professor of law at Washington and Lee University in Virginia, focuses her research on criminal justice and higher education. She tells Health that institutional racism is still prevalent in the United States across just about every sector:

Education

School funding based on property values and residential taxes combined with racial segregation in housing lead to the systemic underfunding of schools attended primarily by Black people. Predominately white districts spend over $2000 more per student than districts where the majority of students are of color. This results in poorer test scores and learning outcomes for Black students.

Housing and health care

"The historical practice of 'redlining' (when banks refused to lend money for mortgages in communities where there were large proportions of people of color because they were considered 'hazardous') is an example of a racist institutional policy still felt today," explains Dr. Beatriz. "Despite redlining being outlawed over 50 years ago, we continue to feel that impact today in so many ways; in 2020, Black Americans were over 40% less likely to own their homes compared to White Americans. This greatly impacts how families accumulate wealth." In 2017, the Urban Institute reported the homeownership rate for white households was 71.9% while the rate for black households was just 41.8%.

Marsha J. Parham-Green, the executive director of the Baltimore County Office of Housing. tells Health that this racial residential segregation is the cornerstone of Black and white disparities. "The inequities built into low-income housing is a fundamental cause of health disparities between blacks and whites," she explains. Housing is one of the vital signs not checked by a doctor, she says, but where a person lives and the conditions of their neighborhood are as important as checking heart rate and blood pressure. "Concentrated poverty, safety and segregation, as well as other social and community attributes further contribute to stress and deterioration of health," she adds. "Those who are most vulnerable, children and the elderly, are most adversely effected by unstable housing conditions."

Faced with high crime, dilapidated housing stock, and the stress and marginalization of poverty, residents of impoverished neighborhoods demonstrate a higher incidence of poor physical and mental health outcomes. These include asthma, depression, diabetes, and heart ailments.

Law and policing

Black people are roughly five times as likely as whites to report having been unfairly stopped by police, Pew Research Center says. Black Americans are also more likely to suffer the ill effects of racial profiling—stereotyping a person on the basis of assumed characteristics or behavior of a racial or ethnic group, rather than on individual suspicion. Experts have studied the psychological effects of racial profiling and found that "victim effects" include post-traumatic stress disorder and other stress-related disorders.

Finance

Kristen E. Broady is the policy director for The Hamilton Project, an economic growth organization, and fellow in economic studies at The Brookings Institution. Her research reveals racial disparities between Black and white households when it comes to nonliquid assets, such as real estate.

Economically based discrimination goes hand-in-hand with institutional racism. For example, business loan officers will require Black applicants to have higher credit scores and income levels than white applicants. It's not surprising, then, that more than half of Black business owners have their loan applications rejected, according to data from the Federal Reserve.

A 2018 investigation by the National Fair Housing Alliance, a Washington, DC-based nonprofit, found economic discrimination when it came to car loans as well. According to the investigation results, on average, non-white testers who experienced discrimination would have paid an average of $2,662.56 more over the life of the loan than less-qualified white testers. And 75% of the time, white testers were offered more financing options than non-white testers.

Politics

As recent as the 2020 presidential election, some state elected officials denied early and mail-in voting. In North Carolina, Black voters' ballots were rejected more than three times the rate of white voters, according to the state's numbers, per a story from ProPublica on September 23.

Attorney and founder of the Mount Vernon Coalition for Police Reform Lauren P. Raysor also explains that the removal of hundreds of sorting machines by the US Postal Service in August 2020 was a form of institutional racism: "Mail delivery was slowed down and residents over-indexing with a Black population couldn't get their mail."

How to fight institutional racism

Both public and private organizations have been taking a hard look at their policies and finding ways to reimagine everything—from creating fairer hiring and recruitment guidelines to working with minority-owned businesses to changing how government funds are spent. Civil rights groups, such as the NAACP, and lawmakers nationwide have called for changes in police policies so they don't target Black people more than white people.

Institutional racism has a negative effect on society. It squashes innovation and creates an environment that breeds unhealthy stress and burnout. It's not good for individuals, and it's not good for businesses from a mental health perspective. If institutional racism continues as status quo, those affected will continue to be a part of a cycle of despair and disenfranchisement. Mental health expert and diversity and inclusion strategist La Shawn M. Paul tells Health that "Black Americans who call out institutional racism are often gaslighted. But to address any problem, you must first acknowledge its existence. Silence is complacency."

Schick believes America can combat institutional racism by making the following changes:

Don't stop with one Black friend and think you know enough about the Black experience. One person does not represent an entire group of people.

Go to town halls, school board meetings, and other places people are discussing solutions. Protests and books are great for creating awareness, but we have awareness now. It's time for solutions at every level.

Speak up when you see changes that can be made. Sometimes the change is in a policy. At other times, it's a small as an individual's behavior.

"It's getting harder for all of us to claim ignorance. It's time to make a change," Schick adds. "And perhaps that is where it begins—with pure intention. Adding courage and action, big changes can occur. But we likely have to do some deep soul searching first and accept that it's going to be uncomfortable. Nevertheless, this is where we must begin. Again."

In the end, we thank you for your good follow-up

Please follow one word to get you all our new subjects.

.webp)

0 تعليقات